॥ શ્રી સ્વામિનારાયણો વિજયતે ॥

॥ THE VACHANAMRUT ॥

Spiritual Discourses

by Bhagwan Swaminarayan

Gadhada II-62

Ātmā-Realization, Fidelity and Servitude

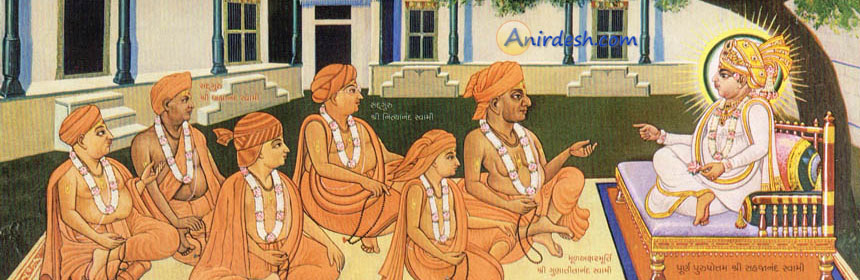

On Māgshar sudi 2, Samvat 1881 [22 November 1824], Swāmi Shri Sahajānandji Mahārāj was sitting on a large, decorated cot on the veranda outside the north-facing rooms of Dādā Khāchar’s darbār in Gadhadā. He was wearing a white khes and had tied a white pāgh around His head. Also, He had covered Himself with a thick, white cotton cloth. At that time, an assembly of munis as well as devotees from various places had gathered before Him.

Shriji Mahārāj then summoned His nephews, Ayodhyāprasādji and Raghuvirji, and said to them, “You may ask Me questions.”

Thereupon Ayodhyāprasādji first asked, “In life, a man may be engrossed in the entanglements of worldly affairs all day long, and during that time, he may well perform some pious as well as impious karmas. Moreover, he may engage in worship for only half an hour or so. Is this enough to burn all of the sins he has committed during the day or not? That is my question.”

Shriji Mahārāj replied, “Even if a person has spent the whole day in pravrutti, and regardless of whatever type of activities he may have been involved in, if, when he engages in the worship of God, his indriyas, antahkaran and jiva all unite and become engrossed in worship, then even if he does so for half an hour, or even for a few minutes, all of his sins will be burnt to ashes. However, if his indriyas, antahkaran and jiva do not unitedly engage in worship, then his sins cannot be burned by worshipping for such a short while. Such a person can attain liberation only by the grace of God. This is the answer to the question.”

Next, Raghuvirji asked a question, “Mahārāj, what must one do for the liberation of the jiva?”

Shriji Mahārāj explained, “If a person aspires for liberation, he should place his body, wealth, home, family and relations in the service of God. Furthermore, he should shun any object that may not be of use in serving God. One who lives such a God-centered life joins the ranks of Nārad and the Sanakādik in the abode of God and attains ultimate liberation after he dies, even if he is a householder. This is the answer to your question.”

Having answered their questions, Shriji Mahārāj then began of His own accord, “Since the day I began pondering over it, I have noticed that there are three inclinations which lead to liberation and which lead to extreme bliss. Of these, one is profound ātmā-realization, which is to believe one’s true self to be the ātmā and engage in the worship of God, like Shukji. The second is the inclination of a woman who observes the vow of fidelity, which is to worship God as if He is one’s husband, just as the gopis did. The third is the inclination of servitude, which is to worship God as His servant, just like Hanumānji and Uddhavji. Without these three inclinations, there is no way in which the jiva can attain liberation. In fact, I, Myself, have firmly cultivated all three of these inclinations. Even if a person possesses one of these inclinations firmly, he becomes absolutely fulfilled.

“I shall now describe the attributes of these three inclinations individually. Firstly, the following are the attributes of one who has realized the ātmā. On one side there is the ātmā and on the other side is the horde of māyā - the body, the indriyas, the antahkaran, the three gunas, the panchvishays, etc. The thought that rests between the two is full of gnān. This thought remains steady, just as the tip of a flame remains steady in the absence of wind. It is this thought which prevents the body, indriyas and antahkaran from becoming one with the ātmā. In fact, even the thought itself does not become one with the ātmā.

“When the jiva attains this thought, its vruttis, which once reached all the way to Kāshi, recede to reach only as far as Vartāl. When that thought is consolidated, the vruttis then recede from Vartāl to reach only as far as Gadhadā. Then, from reaching as far as Gadhadā, they recede and come into the vicinity of the body. From the body, the vruttis recede further and rest in the organs of the indriyas. From the organs of the indriyas, the indriyas’ vruttis turn inward towards the antahkaran. Finally, the vruttis of the indriyas and antahkaran become absorbed in the ātmā. It is then that the jiva’s kāran body, which is full of worldly desires, is said to be destroyed.

“Furthermore, when this thought meets with the ātmā, divine light is generated in the heart of the thinker, and he has the realization of himself as being brahmarup. In addition, he also has the realization of Parabrahma Nārāyan - who resides within that Brahma.1 One who has this realization feels, ‘I am the ātmā, and Paramātmā eternally resides within me.’ Such a sustained state is the highest level of ātmā-realization.

“Secondly, the inclination of a person who has fidelity should be like that of the gopis of Vraj. For example, from the day the gopis touched the holy feet of Shri Krishna Bhagwān, all of the pleasures of this world became like poison to them. In this way, if a faithful wife who has the inclination of fidelity sees a man who is as handsome as Indra, or who is like a deity or some king, then - just as when one sees a rotting dog or some excretion and becomes extremely disgusted and looks away - she would withdraw her eyes. This is the highest form of fidelity. Therefore, if one attaches one’s vruttis to God just as a faithful wife does with her husband, one’s mind would never become pleased upon seeing anyone else.

“Thirdly, a person who has an inclination of offering bhakti with servitude would like the darshan only of his Ishtadev; he would like to hear talks only about Him; he would like His Ishtadev’s nature; and he would also prefer to stay only with Him. Nevertheless, even though he has such love, for the sake of serving his Ishtadev and earning His pleasure, he wishes day and night, ‘If my Ishtadev were to command me, I would follow that command most happily.’ If his Ishtadev were to give a command that would force him to stay far away, he would stay there happily, but in no way would he be disheartened. In fact, he finds supreme bliss in following the command itself. This is the highest level of servitude. Today, Gopālānand Swāmi and also Muktānand Swāmi have such an inclination of offering bhakti with servitude.

“Among the devotees of God who possess one of these three inclinations, there exist three levels - the highest, the intermediate and the lowest. Those who are not found in any one of these categories can only be called wretched. Thus, it is only proper to die after one has thoroughly cultivated one of the three inclinations; it is not appropriate to die if one has not completely developed any single one of the three. Instead, it would be better if a person lives five days longer to dispel his misunderstandings and consolidate at least one of these three inclinations and die thereafter.”

Continuing, Shriji Mahārāj added, “The nature of the jiva is such that when a person is a householder, he would prefer to renounce worldly life; but once he has renounced, he harbors desires for the pleasures of worldly life once again. Such is the perverse nature of the jiva. Therefore, one who is a staunch devotee of God should worship God after discarding such a perverse nature as well as all of one’s personal likes and dislikes. Moreover, it is only appropriate to die after eradicating all desires other than those of God.

“If, however, one does not have intense love for God, one should strengthen only ātmā-realization by thought. Why? Because a devotee of God should either possess resolute ātmā-realization or extremely profound love for God. If a person is not firm in either one of these two inclinations, he should strictly abide by the niyams of this Satsang; only then will he be able to remain a satsangi, otherwise he will fall from Satsang.

“When a devotee of God experiences hardships of any kind, it should be known that the source of those miseries is not kāl, karma or māyā. In actual fact, it is God Himself who inspires hardships to befall upon His devotees in order to test their patience. Then, just as a man hides behind a curtain and watches, God hides in the heart of His devotee, and from there, He observes the devotee’s patience. Besides, who are kāl, karma and māyā that they could harm a devotee of God? So, realizing it to be God’s wish, a devotee of God should remain cheerful.”

Upon hearing this, Muktānand Swāmi asked a question, “Mahārāj, the discourse in which You have just described the three inclinations is very subtle and difficult to put into practice. Only a few can understand it and only a few can actually live by it; not everyone can do so. However, there are hundreds of thousands of people in this Satsang fellowship, and it would be difficult for all of them to understand this principle. So, how can they progress?”

Shriji Mahārāj explained, “If a person behaves as a servant of the servants of a devotee who possesses one of these three inclinations, and if he also follows his commands, then despite not understanding anything else, he would certainly become an attendant of God after this very life and would thus become fulfilled.

“In this world, the glory of God and His Bhakta is indeed very great. After all, no matter how sinful or insignificant a person may be, if he seeks the refuge of God and His Bhakta, that person will become absolutely fulfilled. Such is the greatness of God and His Bhakta. Therefore, one who has received the opportunity to serve God’s Bhakta should remain fearless.”

Finally, Shriji Mahārāj said, “I have delivered this discourse about the three inclinations mainly for the sake of Muktānand Swāmi because I have a great deal of affection for him. So, bearing in mind that Muktānand Swāmi is suffering from an illness, I spoke today so as to be sure that no form of deficiency remains in his understanding.”

In reply, Muktānand Swāmi said, “Mahārāj, I also felt that You delivered this discourse for me.”

Vachanamrut ॥ 62 ॥ 195 ॥

This Vachanamrut took place ago.

FOOTNOTES

1. Here ‘Brahma’ should be understood to mean ‘brahmarup ātmā’.