Show Shravan Audio

Vachanamrut Sar॥ શ્રી સ્વામિનારાયણો વિજયતે ॥

॥ THE VACHANAMRUT ॥

Spiritual Discourses

by Bhagwan Swaminarayan

Gadhada II-55

A Goldsmith’s Workshop

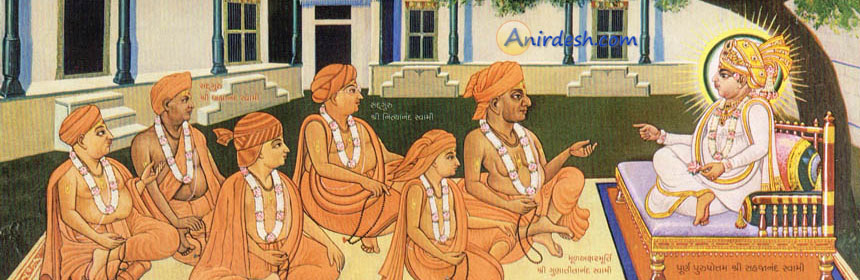

On Jyeshtha sudi 11, Samvat 1880 [7 June 1824], Swāmi Shri Sahajānandji Mahārāj was sitting on a large, decorated cot on the veranda outside the east-facing rooms of Dādā Khāchar’s darbār in Gadhadā. He had tied a golden-bordered, white moliyu from Navānagar around His head. He was wearing a white khes and had covered Himself with a white blanket. At that time, while some munis were singing devotional songs to the accompaniment of a jhānjh and mrudang, other munis as well as devotees from various places had gathered before Him in an assembly.

After the munis had finished singing devotional songs, Shriji Mahārāj said, “Just as one possesses some sort of inclination today, one must also have had some trace of it before joining the Satsang fellowship. Therefore today, I would like all of you to describe whatever type of inclination you have. To begin, I shall describe the type of inclination I have, so please listen.

“Even when I was a child, I very much enjoyed such things as going to mandirs for darshan, listening to spiritual discourses, keeping the company of sādhus, and going on pilgrimages. Then, when I renounced My home, I did not even like to keep clothes. In fact, I liked to stay only in the forest, but I was not the least bit afraid. Even when I came across large snakes, lions, elephants, and countless other types of animals in the forest, there was not the slightest fear of dying in My heart. In this way, I always remained fearless in the dense forest. Thereafter, after travelling to holy places of pilgrimage, I met Rāmānand Swāmi. Only after Rāmānand Swāmi passed away did I begin to keep a little fear - that too, for the sake of Satsang.

“However, the following thought is constantly in My mind: When a person is laid down on his death-bed with death impending, everyone loses their self-interest in that person. The mind of the person who is dying also becomes dejected from worldly life. In the same way, I also constantly feel as if death is imminent at this moment for Myself as well as for others. In fact, I constantly regard each and every worldly object to be perishable and insignificant. Never do I make any distinctions such as, ‘This is a nice object, and this is a bad object.’ Instead, all worldly objects appear the same to Me. For example, when considering the hairs of the armpit, which can be considered good and which bad? Indeed, good or bad, they are all the same. Similarly, all worldly objects appear the same to Me.

“If I do compliment or criticize something, it is only to please the devotees of God. When I say such things as, ‘This is delicious food’, or ‘These are nice clothes’, or ‘This is a beautiful ornament’, or ‘This is a pleasant house’, or ‘This is a fine horse’, or ‘This is a beautiful flower’, it is only to please that particular devotee. In fact, all of My activities are for the sake of the devotees of God; there is not a single activity which I perform for My own personal enjoyment.”

Shriji Mahārāj then said, “The mind of an ekāntik bhakta of God contemplates only upon the form of God; his mouth sings only the praises of God; his hands engage only in the service of God and His devotees; and his ears listen only to the praises of God. In this way, I am able to perform all My activities only after realizing them to be a form of bhakti to God. Besides the bhakti of God, My mind is indifferent to everything else. For example, if the only son of a king dies when the king reaches the age of 60 or 70, the king would become disinterested in all things. In the same manner, I constantly remain disinterested - while eating, drinking, mounting a horse and even when I am pleased or displeased.

“In addition, a thought also remains within My heart that I am the ātmā, distinct from the body; I am not like this body. Also, My mind is always cautious, lest a portion of māyā in the form of rajogun, tamogun, etc. infiltrate My ātmā! In fact, I am constantly vigilant of that.

“Now, consider the following analogy of a goldsmith’s workshop: If a person takes some pure, 24-carat gold to a goldsmith’s workshop but takes his eyes off of it for even a moment, the goldsmith will extract some of the gold and alloy some silver in its place. Similarly, consider the goldsmith’s workshop to be the heart and the goldsmith to be māyā. While the goldsmith is sitting in his workshop - the heart - he is continuously hammering away with his hammer of desires. Even his wife and children secretly steal some gold if they can get their hands on it. Consider the indriyas and antahkaran to be the wife and children of māyā - the goldsmith; after all, it is they who add silver - i.e., the three gunas, attachment to the panchvishays, the belief that one is the body and that one has lust, anger, avarice, etc. - into the chaitanya, i.e., the gold. Not only that, but they also extract some gold in the form of the virtues of gnān, vairāgya, etc.

“When some gold is extracted and silver is mixed in its place, the original gold diminishes in purity to become 18-carat gold. Only if it is melted down can it be purified again. Thus, the silver of rajogun, tamogun, etc., which has been mixed into the jiva should be filtered out. Thereafter, the pure ātmā - the gold - will remain, and no other impurities of māyā will be left. This is the thought in which I remain engrossed, day and night.

“I have thus described My inclination to you. Now, in the same manner, please describe your inclinations to Me.”

Thereupon the sādhus said, “Mahārāj, in no way can there be any impurities of māyā in You, for You are divine. The discourse You have just delivered, in fact, describes our inclinations. Also, the thought that You mentioned is actually what all of us should cultivate in our lives.”

Vachanamrut ॥ 55 ॥ 188 ॥

This Vachanamrut took place ago.