॥ શ્રી સ્વામિનારાયણો વિજયતે ॥

॥ THE VACHANAMRUT ॥

Spiritual Discourses

by Bhagwan Swaminarayan

Kariyani-3

Shuk Muni Is a Great Sādhu; A Person Cannot Be Known by His Superficial Nature

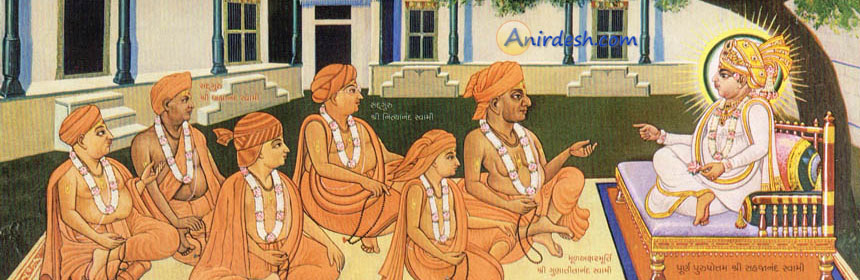

On the evening of Āso vadi 7, Samvat 1877 [28 October 1820], Shriji Mahārāj was sitting facing north on a large, decorated cot on the veranda outside the north-facing rooms of Vastā Khāchar’s darbār in Kāriyāni. He was wearing a white khes and had tied a white feto around His head. He had also covered Himself with a white cotton cloth. At that time, an assembly of paramhansas as well as devotees from various places had gathered before Him.

Thereupon Shriji Mahārāj said, “This Shuk Muni is a very great sādhu. From the day he began staying with Me, his enthusiasm has been ever increasing; in fact, it has never diminished. Thus, he is like Muktānand Swāmi.”

Shriji Mahārāj then continued, “The affection that people develop for each other is due to virtues, and the repulsion they experience for each other is due to faults. But those virtues and faults cannot be discerned from an individual’s superficial behavior. Because, outwardly, a person may walk like a cat, fixing his eyes on the floor as he walks, but inside, he may have intense lust. On seeing him behave in this manner, a person who is not wise would think, ‘He is a very great sādhu.’ On the other hand, someone else may walk with wandering eyes. On seeing him, a person who is not wise would think, ‘He is a fake sādhu.’ Inwardly, however, he may be extremely free of lust. Thus, a person cannot be judged by his superficial, physical behavior; only after staying with him can he be judged. Because by staying with him, his activities can be observed - the way he talks, the way he walks, the way he eats, the way he drinks, the way he sleeps, the way he wakes, the way he sits, etc.

“Also, virtues and vices are more discernible during the period of youth, but they are not so obvious during childhood or during old age. Someone may be spoiled as a child, but as a youth he becomes virtuous. Conversely, someone may be good in his childhood, but becomes spoiled during his youth. A person who is determined in that he feels, ‘It is not good that I am having these base thoughts,’ and who makes an effort to eradicate those thoughts, and who remains determined until they have been eradicated, progresses in his youth. On the other hand, one who is complacent instead of being alert will not progress. So, a virtuous person like the former can be recognized from his childhood.”

Having said this, Shriji Mahārāj talked at length about His own inclination for renunciation in His childhood. He then continued, “One who is virtuous does not like the company of immature children from his childhood; he does not have an appetite for tasty food; and he continuously restrains his body. Just look, when I was a child, I had the same thoughts as Kārtik Swāmi; i.e., I felt, ‘I want to eliminate all of the remnants of My mother - her flesh and blood - from My body.’ So, after many spiritual endeavors, I emaciated My body so much that if something pierced My body, water would come out, but never blood. In this manner, one who is virtuous can be known from his childhood.”

Then Bhajanānand Swāmi asked, “Mahārāj, is it better to maintain such a thought in one’s mind, or is it better to expose the body to austerities?”

To that Shriji Mahārāj said, “Some faults are due to the body - these should be known; and some faults are due to the mind - these should also be known. Of these, which are the faults of the body? Well, repeated erections and itching of the genitals, excessive movement, rapid movement of the eyes, smelling many types of fragrances quickly, walking 20 or 25 miles quickly, embracing someone with such force that his bones break, ejaculating semen during dreams, and so on - all these are faults of the body, not the mind. Even if these faults of the body are greatly reduced, lustful desires, as well as desires for eating, drinking, walking, touching, smelling, hearing and tasting may remain. These should be known as the faults of the mind. So, the faults of the body and mind should be distinguished as just mentioned.

“Then, the faults of the body should be removed by imposing bodily restraints. Thereafter, once the body is weakened, the remaining faults of the mind should be eradicated by contemplating, ‘I am the ātmā, separate from desires. In fact, I am completely blissful.’ One who practices these two methods - bodily restraint and contemplation of the ātmā - is a great sādhu. If one has only bodily restraint, but does not contemplate, then it is not appropriate. Conversely, if one only contemplates but does not restrain one’s body, then that is also not appropriate. Therefore, one who has both is the best. Moreover, if these two methods - bodily restraint and contemplation - are necessary for even householder satsangis to practice, then a renunciant should definitely practice them.”

Then Nishkulānand Swāmi asked, “Mahārāj, can one remain like that through contemplation or through vairāgya?”

Shriji Mahārāj replied, “One remains like that due to the company of a great sādhu. Furthermore, one who is unable to do so even with the company of a great sādhu is a grave sinner.”

Saying that, Shriji Mahārāj continued, “If a renunciant desires to indulge in the worldly pleasures which are appropriate only for a householder, then he is as good as an animal eating dry grass. Why is that? Because even though he is never going to acquire those objects, he still harbors a desire for them. It seems, then, that he has not understood that fact properly, because, as the saying goes, what is the point in asking the name of a village which one is not going to visit? If he does harbor a craving for those objects that he has renounced, will it be possible for him to obtain them during this lifetime? He can attain them only if he falls from Satsang, but not while remaining in Satsang. So, one who maintains a desire for those pleasures while remaining in Satsang is a fool. Why? Because, whoever remains in Satsang is required to comply by its injunctions. For example, if a woman sets out to become a sati but turns back upon seeing the fire, would her relatives allow her to turn back? They would force her to burn on her husband’s funeral pyre. Also, if a Brāhmin lady becomes a widow but continues to dress like a married woman, will her relations allow it? Certainly they would not. Thus, one who maintains indecent swabhāvs while remaining in Satsang has not understood this talk. Because, if he had understood it, such indecent swabhāvs would not remain.”

Saying this, Shriji Mahārāj bid ‘Jai Swāminārāyan’ to everyone and departed to go to sleep.

Vachanamrut ॥ 3 ॥ 99 ॥

This Vachanamrut took place ago.