Show Shravan Audio

Vachanamrut Sar॥ શ્રી સ્વામિનારાયણો વિજયતે ॥

॥ THE VACHANAMRUT ॥

Spiritual Discourses

by Bhagwan Swaminarayan

Gadhada I-38

A Merchant’s Balance Sheet

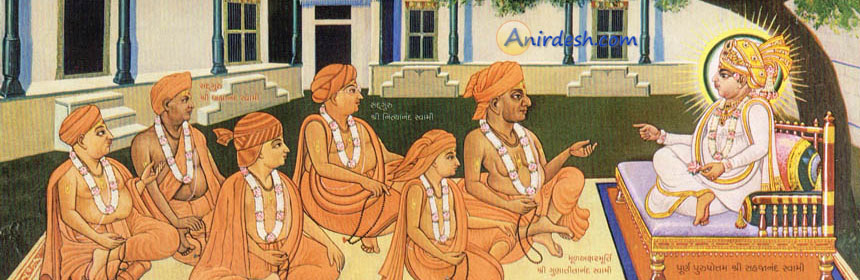

On the evening of Mahā sudi 1, Samvat 1876 [16 January 1820], Shriji Mahārāj was sitting on a small mattress which had been placed on the veranda outside the stables in Dādā Khāchar’s darbār in Gadhadā. He was wearing a white khes and had tied a white, red-bordered feto around His head. He was also wearing a richly embroidered angarkhu and had covered Himself with a thick, white cotton cloth. At that time, an assembly of sādhus as well as devotees from various places had gathered before Him.

After glancing at all of the devotees, Shriji Mahārāj thought for a considerable length of time and said, “Please listen, I have something to say.” He then continued, “From the time a satsangi enters the Satsang fellowship, he should examine his mind by thinking, ‘In the first year, my mind was like this; then it was like this. Previously, I had this much desire for God and this much desire for the world.’ In this manner, he should repeatedly reflect on this yearly total of desires and always strive to gradually, yet constantly eradicate all worldly desires that remain in his mind. If, however, he does not introspect in this manner and allows those desires to accumulate, then they will never be overcome. Consider, for example, the analogy of opening an account with a merchant. If one settles one’s debts to him regularly on a monthly basis, then it would not be difficult to repay the debt. But if one waits to pay until the end of the year, it would be extremely difficult to settle the account. Likewise, one should introspect constantly.

“In reality, the mind is saturated with desires for the world. But, in the manner in which sesame seeds are imbued with scent by padding them between alternating layers of flowers, the mind should be similarly saturated with flowers in the form of the constant remembrance of God’s divine actions and incidents - coupled with an understanding of His greatness. The mind should constantly be entangled in a web in the form of these divine actions and incidents of God, and thoughts of God should be constantly conceived in the mind. As one thought subsides, another thought should be conceived. As the second subsides, a third should be conceived. In this manner, the mind should not be left idle.” Saying this, Shriji Mahārāj narrated the example of the ghost in detail.

Thereafter, He continued, “Even if one begins to recall the divine incidents, discourses and darshan of God of just one day in this manner, there would be no end to them. If that is so, then there would certainly be no end to them for one who has passed ten to fifteen years in Satsang.

“These divine actions and incidents should be recalled in the following manner: ‘Mahārāj and the paramhansas held an assembly in this village, in this manner; puja was offered to Mahārāj in this manner; and discourses took place in this manner, etc.’ Those divine incidents of God should be recalled over and over again. Moreover, for one who does not understand much, this is certainly the best method. In fact, there is no other method like it.

“Then you may say, ‘We will eat a little amount and observe many fasts.’ But I do not stress those methods. One should abide by those methods as best as one can according to one’s given niyams. But what is truly to be done is what I have just described to you.”

Thereafter, Shriji Mahārāj said, “I believe that the mind should be free of worldly desires. No matter how much pravrutti a person may do physically, if his mind is pure, then he cannot be seriously harmed - even though outwardly, in society, a person engaged in pravrutti appears to be discreditable. On the other hand, if a person’s mind is full of worldly desires and he superficially behaves as if he is practicing nivrutti, then he may appear respectable in society, but his jiva will suffer severely. Why? Because at the time of death, it is those thoughts that are in one’s mind that spring forth, just like the fawn sprang forth in Bharatji’s mind during his last moments. As a result, he became a deer in his next life, even though he had originally renounced a kingdom and Rushabhdev Bhagwān was his father. Therefore, to remain free of worldly desires mentally is My principle. By observing fasts, the mind does become weak along with the body, but when the body becomes robust again, the mind becomes robust as well. Therefore, mental renunciation is required along with physical renunciation. In fact, one whose mind entertains thoughts of God but not thoughts relating to the world should be considered eminent in our Satsang fellowship. Conversely, those who do not do this are inferior.

“Furthermore, a householder should engage in worldly activities physically, but mentally - just like the renunciant - he should also remain free of worldly desires and should contemplate on God. Also, he should engage in social activities according to the command of God. Moreover, if mental renunciation is not genuine renunciation, then what about King Janak, whose mind was like that of a great yogi master despite ruling a kingdom? Therefore, only renunciation which is cultivated mentally is appropriate.”

Shriji Mahārāj then explained, “If impure thoughts arise in one’s mind, one should reveal them. But, as the saying goes, ‘Only a dog would lick a dog’s face;’ or ‘Sarpne gher parono sāp, mukh chātine valiyo āp;’1 or when a married woman goes to a widow, the widow says, ‘Come, lady, May you also become like me’ - similarly, to reveal one’s thoughts to a person who also experiences impure thoughts like oneself is like the aforesaid examples. To whom, then, should one reveal one’s impure thoughts? Well, one should reveal them to a person who is so strong-willed that no impure thoughts relating to the world arise in his mind. However, there may be many who do not experience such thoughts. So, out of those, one should reveal one’s impure thoughts to a person who denounces those thoughts after listening to them and who continues to denounce them in all of one’s activities, i.e., while eating, drinking, sitting, standing, etc. - until they are eradicated from one’s mind. Moreover, that person should have the same determination to eradicate others’ impure thoughts as he has to remove his own. One should reveal one’s impure thoughts to such a person. But if the person to whom one reveals one’s impure thoughts does not counsel in this manner and is himself careless, then what can one gain from him? Therefore, after revealing one’s impure thoughts in this way and eradicating them, one should continuously harbor thoughts only of God and become free from all desires for the pleasures of the world.”

Thereafter, Shriji Mahārāj said, “What are the characteristics of observing a fast on the day of Ekādashi? Well, the ten indriyas and the mind, the eleventh, should be withdrawn from their respective vishays and attached to God. That is considered as having observed Ekādashi. In fact, devotees of God should engage in this observance continuously. In comparison, if a person whose mind is not free from worldly desires in this way engages in observances and austerities physically, he does not benefit very much. Therefore, observing his own dharma and understanding God’s greatness, a devotee of God should maintain a constant effort to free his mind of worldly desires.”

Shriji Mahārāj then explained, “A true renunciant is one whose mind never entertains a desire for objects that he has already renounced. Just as one harbors no desire for feces once they have been excreted, similarly, no desire arises for renounced objects; thus the related verse which Nāradji narrated to Shukji: ‘Tyaja dharmam-adharmam cha ... ||.’2 The essence of that verse is: ‘Renouncing all objects except the ātmā, one should behave only as the ātmā and worship God.’ Such a person can be called a perfect renunciant. Furthermore, householder devotees should behave in the manner of King Janak, who said, ‘Although my city of Mithilā is burning, nothing of mine is burning.’ Thus the verse: ‘Mithilāyām pradeeptāyām na me dahyati kinchana ||.’3 A householder devotee with this type of understanding, even though he may possess a house, is a true devotee. One who is not such a renunciant or such a householder is called a pseudo-devotee, whereas one who does behave as described above should be known as an ekāntik bhakta.”

Thereafter, Motā Ātmānand Swāmi asked Shriji Mahārāj, “What are the characteristics of the jivātmā, which is distinct from the body, the indriyas, the antahkaran and their presiding deities?”

Shriji Mahārāj replied, “I shall answer that question in brief. The jiva is the speaker that elaborates on the nature of the body, the indriyas, etc., and explains their natures separately to the listener. That speaker also endorses the body, indriyas, etc.; it is the knower and is distinct from all of the above - that is called the jiva. Also, the listener, which understands the forms of the body, indriyas, etc., as being distinct, which endorses them, which knows them and which is distinct from them all is also known as the jiva itself. This is the method of understanding the nature of the jiva.”4 Shriji Mahārāj spoke in this manner.

Vachanamrut ॥ 38 ॥

This Vachanamrut took place ago.

FOOTNOTES

1. સર્પને ઘેર પરોણો સાપ, મુખ ચાટીને વળિયો આપ.

When a snake becomes a guest to another snake, as the host is also a snake and will have nothing to offer, the guest snake’s reward will be nothing more than an opportunity to lick the host’s face.

2. त्यज धर्ममधर्मं च...। - Mahābhārat: Shānti-parva, Moksh-dharma 33.40

3. मिथिलायां प्रदिप्तायां न मे दह्यती किंचन॥ - Mahābhārat: Shānti-parva, Moksh-dharma 18.40

4. The jiva is a chaitanya entity, meaning it possesses consciousness. The body, the indriyas, the antahkarans, etc. are jad, meaning they do not possess consciousness. Therefore, the jiva that resides in the body itself explains to itself using the indriyas, the antahkarans, etc. Moreover, it itself listens in order to understand. In this manner, the jiva is the knower of the body, the indriyas, man, prāns, and buddhi; it is the one who develops conviction, one who sees, one who listens, one who speaks, one who tastes, one who smells, one who contemplates, etc. One should understand that that is one’s true form.