Show Shravan Audio

Vachanamrut Sar॥ શ્રી સ્વામિનારાયણો વિજયતે ॥

॥ THE VACHANAMRUT ॥

Spiritual Discourses

by Bhagwan Swaminarayan

Gadhada I-70

Kākābhāi’s Question; A Thief Injured by a Thorn

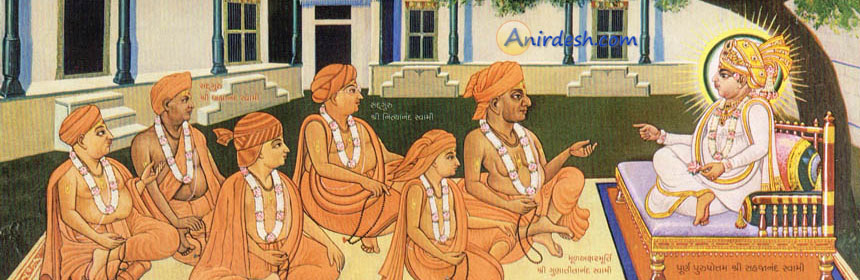

On Chaitra sudi Punam, Samvat 1876 [29 March 1820], Shriji Mahārāj was sitting on a large, decorated cot on the veranda outside the east-facing rooms of Dādā Khāchar’s darbār in Gadhadā. He had tied a white cloth with a border of silken thread around His head. He was wearing a white khes and had also covered Himself with a white cotton cloth. With His hand, He was turning a rosary of tulsi beads. At that time, an assembly of paramhansas as well as devotees from various places had gathered before Him.

Then Shriji Mahārāj said, “The senior paramhansas please ask each other questions; or if a householder has a question, he may ask the paramhansas.”

Thereupon Kākābhāi, a devotee from the village of Rojkā, asked Nityānand Swāmi, “Deep within one’s heart, something beckons one to indulge in the vishays, while something else dissuades one from indulging in them, saying no. What is it that says no, and what is it that says yes?”

Nityānand Swāmi replied, “It is the jiva that says no and the mind that says yes.”

Shriji Mahārāj then said, “Allow Me to answer that question.1 From the very day we began to understand and realized who our parents were, they have indoctrinated into us the following: ‘This is your mother and this is your father; this is your paternal uncle and this is your brother; this is your maternal uncle and this is your sister; this is your maternal aunt and this is your paternal aunt; this is your mother’s sister and this is your buffalo; this is your cow and this is your horse; these are your clothes and this is your house; this is your mansion and this is your farm; these are your ornaments,’ and so on. These words of kusangis have been imprinted in the mind. How are they imprinted? Well, it is rather like the small piece of glass that women attach into works of embroidery - the mind represents the embroidery, and the jiva represents the piece of glass. In this manner, the words and the sights of those kusangis, along with the other types of vishays, have become imprinted in the mind.

“Then, after that person enters the Satsang fellowship, the Sant talks about the glory of God, denounces the vishays, and also explains that the world is perishable. Thereby, the words and the sight of the Sant dwell in the person’s mind.

“Analogously, then, there are two armies facing each other. In the battlefield of Kurukshetra, for example, the armies of the Kauravs and the Pāndavs stood facing each other and fought with arrows, spears, projectiles, artillery and chains. Some fought with swords, some with maces, others with their bare hands. In the process, some lost their heads, others injured their thighs and many were slaughtered. In the same way, in the person’s antahkaran are the forms of the kusangis standing armed with their weapons, i.e., the panchvishays; as well as the form of the Sant standing armed with weapons in the form of words such as, ‘God is satya; the world is perishable; and the vishays are false.’ A mutual conflict thus exists between these two sets of words. When the force of the kusangis prevails, a desire to indulge in the vishays arises; when the force of the Sant prevails, the desire to indulge in the vishays disappears. In this way, there is a conflict within the antahkaran. Hence the verse:

Yatra yogeshvaraha krushno yatra partho dhanur-dharaha |Tatra shreer-vijayo bhootir-dhruvā neetir-matir-mama ||2

“This verse explains: ‘Where there is Yogeshwar - Shri Krishna Bhagwān - and where there is the great archer Arjun, only there do Lakshmi, victory, divine powers and resolute morality exist.’ Therefore, one should have a firm conviction that victory belongs to the one on whose side these sādhus happen to be.”

Kākābhāi then asked further, “Mahārāj, by what means can the force of the Sant increase and the force of the kusangis decrease?”

To this Shriji Mahārāj replied, “The kusangis residing within and those residing externally are both one. Also, the Sant residing within and the one residing externally are both one. Now, the force of the internal kusangis increases with the nurturing of the external kusangis. In the same way, the force of the Sant within increases with the nurturing of the Sant residing externally. Therefore, by avoiding the company of external kusangis and by keeping the company of only the Sant residing externally, the force of the kusangis decreases and the force of the Sant increases.” That is how Shriji Mahārāj answered that question.

Again, Kākābhāi asked, “Mahārāj, on the one hand, there is a person who has overcome the fight against kusangis, and for whom only the force of the Sant is predominant. On the other hand, there is another person whose conflict is still ongoing. Of the two, when the former dies, there is no doubt that he will attain the abode of God. But please tell us what will be the fate of the latter - whose conflict is still ongoing - when he dies?”

Shriji Mahārāj explained, “On waging war, one person may face Vāniyās or someone from a weak caste. Consequently, he may win easily. Another person, however, is confronted by a battalion of Arabs, Rajputs, Kāthis and Kolis - who are very difficult to conquer, certainly not as easy to defeat as the Vāniyās. Therefore, his fight continues. If, in the process of such fighting, he wins, then all is well and good. But if while fighting he does not give in to his opponents - despite their attempts - and if he were to die at that time, would his master not be aware of his valiant efforts? Would He not appreciate that, compared to the one who faced the easy opposition of the Vāniyās, this person faced formidable opposition that was difficult to overcome? The master would indeed be well aware of both situations. In the same way, God is sure to help such a person as you have described. He would believe, ‘This person is faced with the overwhelming force of fluctuating thoughts, yet he is still putting up a gallant fight. Therefore, he deserves to be congratulated.’ Realizing this, God does help him. For this reason, then, one should remain carefree and not worry in the least. One should continue to worship God in the same fashion, keep the Sant predominant, and stay away from kusangis.” Shriji Mahārāj thus replied in a joyful manner.

Thereafter, Jivābhāi of the village Jaskā asked Nityānand Swāmi, “How does unfaltering faith in God develop?”

Nityānand Swāmi replied, “If one avoids the company of kusangis and constantly keeps the company of sādhus, then by listening to the talks of those sādhus, unfaltering faith in God will develop. However, if one keeps the company of kusangis, such unfaltering faith will not develop.”

Again Shriji Mahārāj said, “Allow Me to answer that question.” Continuing, He said, “One should cultivate faith in God for the sole purpose of the liberation of one’s jiva, but not out of a desire for some material object.3 For example, ‘If I practice satsang, my ill body will recover,’ or ‘As I am childless, may I get a son,’ or ‘As my sons are dying, may they stay alive,’ or ‘Since I am poor, may I become rich,’ or ‘If I do satsang, I will regain my lost assets.’ One should not practice satsang harboring desires for such material gains. If one does practice satsang while nourishing such desires, then one may become a very staunch satsangi if those desires are fulfilled; but if one’s desires are not fulfilled, one’s faith will diminish. Therefore, one should practice satsang solely for the liberation of one’s jiva; one should not harbor any desire whatsoever for any material objects.

“Besides, if there are ten members in a household and all ten are faced with death, then is it a small feat if even one is saved?4 Or if one was destined to have to beg for food but received a rotlo to eat instead, is that a small feat? In these cases, one should believe that although everything was going to be lost, at least this much has been saved! In the same way, even if extreme misery is due to befall one, that misery would certainly decrease slightly if one were to keep the refuge of God. The jiva, however, fails to understand this. It is as if one who is to be executed on a shuli gets away with the suffering of a mere pinprick. Such is the difference.

“There is a story illustrating this: Many thieves lived in a particular village. One of these thieves often kept the company of a sādhu. Once, while the thief was on his way to visit the sādhu, a thorn pierced his foot, penetrating it completely. As a result, his foot became swollen and he was unable to accompany the other thieves to steal. The other thieves, who went to steal, broke into a king’s treasury and escaped with a great deal of money, which they duly shared among themselves. Naturally, a lot of money came their way. On hearing this news, the parents, wife and relatives of the thief who used to sit with the sādhu and who was injured scolded him: ‘Because you went to the sādhu instead of going to steal, we lost out. The thieves who did go to steal returned with a lot of money.’ Meanwhile, the king’s army arrived, arrested all of the thieves and took them away to be executed on a shuli. The injured thief was also caught and consigned to execution. However, all of the villagers and the sādhu bore witness, ‘This particular man was not involved in the theft as he had been hurt by a thorn.’ The thief was thus released.

“In the same way, if a person who practices satsang were to face the suffering of being executed on a shuli, it would be reduced to the pain of a mere thorn-prick. After all, I have asked of Rāmānand Swāmi, ‘If your satsangi is destined to suffer the distress inflicted by the sting of one scorpion, may the distress of the stings of millions and millions of scorpions befall each and every pore of my body; but no pain should afflict your satsangi. Moreover, if the begging bowl is written in the prārabdha of your satsangi, may that begging bowl come to Me; but on no account should your satsangi suffer from the lack of food or clothing. Please grant Me these two boons.’ I asked this of Rāmānand Swāmi, and he happily granted it to Me. Therefore, even if worldly miseries are destined to befall anyone practicing satsang, they do not.

“Even so, material objects are all temporary. So if a person practices satsang entertaining desires for such objects, then doubts will certainly cloud his faith. Therefore, other than the desire for the liberation of one’s own jiva, one should practice satsang having no desires whatsoever. Only then will unfaltering faith develop.”

This is only a portion of the detailed discourse delivered by Shriji Mahārāj.

Vachanamrut ॥ 70 ॥

This Vachanamrut took place ago.

FOOTNOTES

1. The man (mind) is an instrument to acquire gnān - knowledge. Therefore, as long as the jiva has not acquired the knowledge of this world, panchvishays, etc., the jiva will not be able to separate from the mind. The mind and the jiva are bound to each other like the tamarind seed is fused with its shell. Therefore, while the jiva is still acquiring knowledge, it is not possible for the jiva to say no and mind to say yes since the jiva and mind are one. Therefore, Shriji Maharaj answers the question because Nityanand Swami’s answer is inadequate.

2. यत्र योगेश्वरः कृष्णो यत्र पार्थो धनुर्धरः।

तत्र श्रीर्विजयो भूतिर्ध्रुवा नीतिर्मतिर्मम॥ - Bhagwad Gitā: 18.78

3. Even if one refrains from bad company and maintains the association of the Satpurush, if one develops conviction of God due to some desires, then if that desire is not fulfilled, conviction of God may become uprooted completely. Since Nityanand Swami’s lacks this explanation, Shriji Maharaj answers to completely answer the question. Conviction developed only for the sake of one’s liberation becomes stable and firm, whereas conviction developed due to some desires never remains firm.

4. Gunatitanand Swami explains these words by Shriji Maharaj: “When wealth is lost, one’s son dies or one cannot find food to eat, then at such times understanding helps. Once, a businessman went abroad and returned with a ship full of ten million gold coins. When he placed his foot on the plank leading to the shore to disembark, the ship sank. Then the businessman said, ‘Oh! What a misfortune.’ But then he reasoned, ‘When I was born, did I have any gold?’ Similarly, a mendicant found a rope while walking on the road. He kept it on his shoulder, but it slipped off. Then, after he had walked a little distance, he realized it fell. Then he said, ‘Never mind. Mujku rassā pāyā ja no’tā – I never had the rope in the first place.’ Thus, think in this way and remain happy. Also, in the Kakabhai’s Vachanamrut (Gadhada I-70) it is said that if there are ten people in the house and all of them are destined to die, but then if one of them is saved, is that too little? Thus, understand in this way.”